In December 1772, Governor Thomas Hutchinson, of the

Massachusetts Bay Colony, went on vacation with his family in his country home

in Milton. While there, he spent most

his time preparing a speech for the upcoming new year to address the rights of

the colonists under the British Government in response to much of the political

upheaval that had occurred due to new policies and taxes coming from Parliament

ever since the mid-1760’s.

Thomas Hutchinson would deliver his speech when the General

Court, the legislative branch of the Massachusetts colonial government,

returned to session on January 6, 1773. Hutchinson

addressed the General Court and acknowledged to them his awareness of the

disorder of the government in Massachusetts over new policies coming directly

from the British Parliament without consent from the colonies. Governor Hutchinson had hoped that the

violence and upheaval within the colony would subside but it had by this time

become clear to him that the problem needed to be addressed if it were to be

resolved. In his speech, Hutchinson

argued:

“…When our predecessors first took

possession of this plantation, or colony, under a grant and charter from the

Crown of England, it was their sense, and it was the sense of the kingdom, that

they were to remain subject to the supreme authority of Parliament. This appears from the charter itself, and

other irresistible evidence.”

In other words, by moving from the mother country to unknown

lands, the colonists did not escape the duties owed to the mother country and

the laws that applied to the entire empire.

By accepting the protection of the mother country while settling in

distant lands, the colonists had long ago consented to adhere to the laws that

came forth from Parliament regardless of representation. In Hutchinson’s view, that had continued to

be the case from the time in which the colony had first settled, up until the

1770’s.

Governor Hutchinson feared that by offering the mother

country an ultimatum that the colonists either be allowed representation or

just be allowed to govern themselves independently would estrange the mother

country from its colonies, creating a whole new and separate government rather

than remaining part of the British Empire:

“I know of no

line that can be drawn between the supreme authority of Parliament and the

total independence of the colonies: it is impossible there should be two

independent Legislatures in one and the same state; for, although there may be

but one head, the King, yet the two Legislative bodies will make two

governments as distinct as the kingdoms of England and Scotland…”

His fear of the colonies breaking away from the mother

country in this regard stemmed from the idea that as an independent government the

colonists would lose the protection of a strong and stable country and could

easily be subjected to being over taken by other countries such as Spain or

France, at which point the colonists would lose their rights as Englishmen

altogether, and would have to adapt to the stricter rules and regulations that

might be put on the subjects of other countries. Hutchinson even felt that subjects in one

colony or empire did not all have access to the same rights and policies as

other subjects within an empire. He

argued that even within the democratic nature of election of representatives,

the colonists agreed to give up some of their rights to the individual elected;

whether it was they themselves who voted for that individual or if they were a

part of the minority who voted against him.

Once a man was elected into office to speak as the voice of the people,

the individual people gave up their rights to the one man who was elected to

act as the group voice for them. As not

every man elected would have the same ideas and motives, this would mean that

each colony would have different laws and ideas of what the rights of

Englishmen really were, all based off of their elected officials and the way

each colony adapted to them. Therefore,

what one colony may have the right or privilege to do may not be the same as

other colonies within the empire, and in extension, what the subjects in the

mother country had the rights and privileges to do, did not necessarily have to

be the same rights and privileges that were extended to the colonies.

Despite all of this, Governor Hutchinson did acknowledge

that governments do make mistakes, that no one governing entity is

perfect. As a result, he felt that to

question policies that came out of one’s government was healthy. He just did not agree with the mode of questioning

policies which the colonists had adopted: through violent rioting, and

questioning the superiority of the mother country over the colonies every time

there was a new policy they did not agree with.

Instead, Hutchinson argued, there had to be healthier and more

constitutional channels through which to question the offending policies:

“I have no desire, gentlemen, by

anything I have said, to preclude you from seeking relief, in a constitutional

way, of any cases in which you have heretofore, or may hereafter suppose that

you are aggrieved; and, although I should not concur with you in sentiment, I

will, notwithstanding, do nothing to lessen the weight which your

representations may deserve.”

In making this speech, Governor Hutchinson had hoped to have

adopted a middle ground between Parliament and the colonists: acknowledging to

Parliament that they still had full superiority over the colonies while

acknowledging the right of the colonists to question policies when they feel

their government has been in error.

Unfortunately for Governor Hutchinson, his speech was too little too

late. By this time, the colonists had

already traveled too far down the channel of independence, and Parliament had adopted

beliefs that if they ignored the upheaval in the colonies, it would eventually

blow over. Therefore, when Parliament

heard of Governor Hutchinson’s speech, instead of supporting him, they condemned

his speech for bringing a problem which they hoped would die away back to the

forefront of the minds of the colonists.

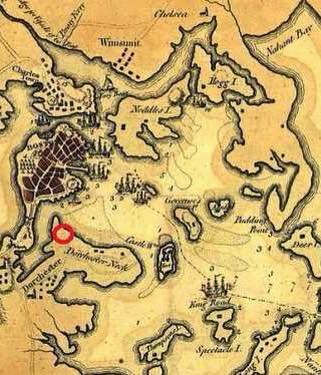

"The wicked Statesman, or the Traitor to his country, at the Hour of DEATH"

Depicting Thomas Hutchinson being tormented and judged by death while under his arm is a list representing the salary the governor collected from the Tea Tax